Connected speech is a fundamental aspect of spoken English that often goes unnoticed by learners. It refers to the way words blend and link together in continuous speech, rather than being pronounced in isolation.

Figuring out connected speech is crucial for improving both your listening comprehension and your spoken fluency. This article aims to provide a comprehensive guide to connected speech, covering its various phenomena, rules, and practical applications.

Whether you’re a beginner or an advanced learner, this guide will equip you with the knowledge and skills to navigate the complexities of spoken English with confidence.

By understanding how sounds change and interact in connected speech, learners can significantly improve their ability to understand native speakers and communicate more naturally. This guide provides detailed explanations, numerous examples, and practical exercises to help learners master this essential aspect of English pronunciation.

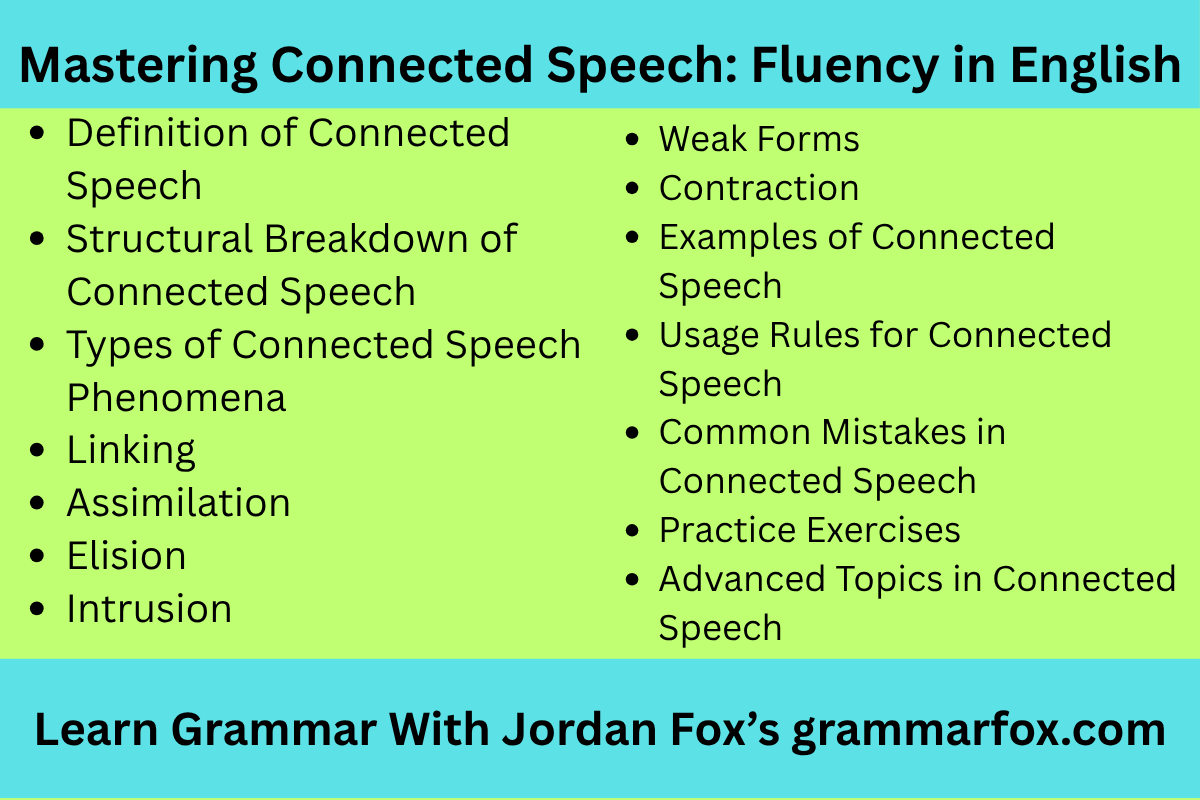

Table of Contents

- Definition of Connected Speech

- Structural Breakdown of Connected Speech

- Types of Connected Speech Phenomena

- Examples of Connected Speech

- Usage Rules for Connected Speech

- Common Mistakes in Connected Speech

- Practice Exercises

- Advanced Topics in Connected Speech

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Conclusion

Definition of Connected Speech

Connected speech refers to the way spoken language occurs in a continuous sequence, where words are joined to form a stream of sounds. In connected speech, words are not pronounced in isolation, as they often are in written form or in pronunciation exercises. Instead, the sounds of words blend together, change, or even disappear, creating a smoother and more efficient flow of communication. This blending and modification of sounds is governed by various phonetic processes that aim to simplify pronunciation and maintain a consistent rhythm.

Understanding connected speech is essential for effective listening comprehension. Native speakers naturally use connected speech, and if you are not familiar with its patterns, you may struggle to understand what they are saying, even if you know all the individual words.

Moreover, mastering connected speech will significantly enhance your own spoken fluency, making your speech sound more natural and effortless.

Connected speech is not simply sloppy or incorrect pronunciation. It is a systematic and rule-governed aspect of spoken language.

Learning to recognize and use the patterns of connected speech is a crucial step towards achieving proficiency in English.

Structural Breakdown of Connected Speech

The structure of connected speech involves several phonetic processes that modify the pronunciation of words. These processes are driven by the need to reduce articulatory effort and maintain a smooth flow of speech.

Here’s a breakdown of the key elements:

- Phonetic Environment: The sounds surrounding a word influence its pronunciation. The sounds before and after a word can cause changes in its initial or final sounds.

- Stress and Rhythm: English is a stress-timed language, meaning that stressed syllables occur at roughly equal intervals. Unstressed syllables are often shortened or weakened, leading to the use of weak forms.

- Articulatory Ease: Speakers tend to minimize the effort required to produce speech. This often results in sounds being assimilated to nearby sounds or being elided altogether.

- Intonation: The rise and fall of pitch in speech can also affect the pronunciation of individual words. For example, words at the end of a phrase may be lengthened or emphasized.

These elements interact to create the characteristic sound of connected speech. By understanding how they work, learners can begin to predict and recognize the patterns of connected speech.

Types of Connected Speech Phenomena

There are several distinct phenomena that contribute to connected speech. Each of these has its own characteristics and rules.

Linking

Linking occurs when the final sound of one word is joined to the initial sound of the next word. This is particularly common when a word ends in a consonant sound and the next word begins with a vowel sound. There are different types of linking, including consonant-vowel linking, vowel-vowel linking (with intrusive sounds), and linking /r/.

Consonant-Vowel Linking: This is the most common type of linking, where the final consonant sound of one word is pronounced at the beginning of the next word if it starts with a vowel sound.

Vowel-Vowel Linking: When a word ends in a vowel sound and the next word begins with a vowel sound, a linking sound (often /j/ or /w/) may be inserted to separate the vowels and make the transition smoother.

Linking /r/: In non-rhotic accents (where the /r/ sound is not pronounced after a vowel at the end of a word, such as in many British accents), the /r/ sound is pronounced if the next word begins with a vowel sound.

Assimilation

Assimilation is the process by which a sound changes to become more like a neighboring sound. This can involve changes in place of articulation, manner of articulation, or voicing.

- Place Assimilation: A sound changes its place of articulation to match that of a neighboring sound. For example, the /n/ in “in” may become /m/ before /p/ or /b/ (e.g., in particular becomes im particular).

- Manner Assimilation: A sound changes its manner of articulation to match that of a neighboring sound.

- Voicing Assimilation: A voiceless sound becomes voiced, or vice versa, to match a neighboring sound.

Elision

Elision is the omission of a sound in connected speech. This often occurs with weak consonants or vowels, particularly at the end of words or in unstressed syllables.

- Consonant Elision: A consonant sound is dropped, often at the end of a word when followed by another consonant sound.

- Vowel Elision: A vowel sound is dropped, often in unstressed syllables.

Intrusion

Intrusion is the insertion of an extra sound between two words to make the transition smoother. The most common intrusive sounds are /j/, /w/, and /r/.

- Intrusive /r/: In non-rhotic accents, an /r/ sound is inserted between a word ending in a vowel and the next word beginning with a vowel.

- Intrusive /j/ and /w/: These sounds are inserted between vowels to separate them and make the transition easier.

Weak Forms

Weak forms are the reduced pronunciations of grammatical words (such as articles, prepositions, auxiliary verbs, and pronouns) in unstressed positions. These words are often pronounced with a schwa /ə/ or a reduced vowel sound.

Examples of words that commonly have weak forms include a, an, the, to, of, for, at, from, is, are, was, were, has, have, had, do, does, did, can, could, shall, should, will, would, must, he, him, his, she, her, hers, we, us, our, they, them, their, theirs, and you.

Contraction

Contractions are shortened forms of words or phrases, where one or more sounds are omitted and an apostrophe is used to indicate the missing letters. Contractions are very common in both spoken and written English, especially in informal contexts.

Examples include I’m (I am), you’re (you are), he’s (he is/has), she’s (she is/has), it’s (it is/has), we’re (we are), they’re (they are), isn’t (is not), aren’t (are not), wasn’t (was not), weren’t (were not), haven’t (have not), hasn’t (has not), hadn’t (had not), don’t (do not), doesn’t (does not), didn’t (did not), can’t (cannot), couldn’t (could not), won’t (will not), wouldn’t (would not), shouldn’t (should not), and mustn’t (must not).

Examples of Connected Speech

The following tables provide examples of each type of connected speech discussed above. These examples will help you recognize and understand these phenomena in real-life speech.

Table 1: Linking Examples

This table illustrates how linking connects words, particularly when a consonant sound is followed by a vowel sound.

| Phrase | Connected Speech Pronunciation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| an apple | /ən ˈæpl̩/ | The /n/ sound at the end of “an” is linked to the vowel sound at the beginning of “apple.” |

| turn off | /ˈtɜːn ɒf/ | The /n/ sound at the end of “turn” is linked to the vowel sound at the beginning of “off.” |

| look at | /ˈlʊk æt/ | The /k/ sound at the end of “look” is linked to the vowel sound at the beginning of “at.” |

| far away | /ˌfɑːr əˈweɪ/ (rhotic), /ˌfɑː əˈweɪ/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

| go out | /ˌɡoʊ ˈaʊt/ (with intrusive /w/) | An intrusive /w/ may be inserted between the /oʊ/ and /aʊ/ sounds. |

| see it | /ˈsiː ɪt/ (with intrusive /j/) | An intrusive /j/ may be inserted between the /iː/ and /ɪ/ sounds. |

| the end | /ði ˈɛnd/ | The /i/ sound at the end of “the” is linked to the vowel sound at the beginning of “end.” |

| my eye | /maɪ ˈaɪ/ (with intrusive /j/) | An intrusive /j/ may be inserted between the /aɪ/ and /aɪ/ sounds. |

| do it | /duː ɪt/ (with intrusive /w/) | An intrusive /w/ may be inserted between the /uː/ and /ɪ/ sounds. |

| for ages | /fɔːr ˈeɪdʒɪz/ (rhotic), /fɔː ˈeɪdʒɪz/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

| more often | /mɔːr ˈɒfən/ (rhotic), /mɔː ˈɒfən/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

| law and order | /ˌlɔːr ænd ˈɔːrdər/ (rhotic), /ˌlɔː ænd ˈɔːdə/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

| is easy | /ɪz ˈiːzi/ | The /z/ sound at the end of “is” is linked to the vowel sound at the beginning of “easy.” |

| has always | /hæz ˈɔːlweɪz/ | The /z/ sound at the end of “has” is linked to the vowel sound at the beginning of “always.” |

| was open | /wɒz ˈoʊpən/ | The /z/ sound at the end of “was” is linked to the vowel sound at the beginning of “open.” |

| were able | /wɜːr ˈeɪbl/ (rhotic), /wɜː ˈeɪbl/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

| here is | /hɪər ɪz/ (rhotic), /hɪə ɪz/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

| there are | /ðɛər ɑːr/ (rhotic), /ðɛə ɑː/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

| four eggs | /fɔːr ɛɡz/ (rhotic), /fɔː ɛɡz/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

| your own | /jʊər oʊn/ (rhotic), /jʊə oʊn/ (non-rhotic with intrusive /r/) | In rhotic accents, the /r/ is pronounced. In non-rhotic accents, an intrusive /r/ may be added. |

Table 2: Assimilation Examples

This table provides examples of how sounds change to become more similar to neighboring sounds.

| Phrase | Connected Speech Pronunciation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| in possible | /ɪm ˈpɒsɪbl̩/ | The /n/ in “in” changes to /m/ because of the following /p/. (Place Assimilation) |

| in big | /ɪm ˈbɪɡ/ | The /n/ in “in” changes to /m/ because of the following /b/. (Place Assimilation) |

| ten bikes | /tɛm ˈbaɪks/ | The /n/ in “ten” changes to /m/ because of the following /b/. (Place Assimilation) |

| good boy | /ɡʊb ˈbɔɪ/ | The /d/ in “good” changes to /b/ because of the following /b/. (Place Assimilation) |

| have to | /ˈhæftə/ or /ˈhæftuː/ | The /v/ in “have” is often dropped, and /t/ assimilates to /f/. (Manner and Elision) |

| used to | /ˈjuːstə/ | The /d/ in “used” is often dropped when followed by “to.” (Elision) |

| want to | /ˈwɒnə/ | The /t/ in “want” is elided, and “to” becomes /ə/. (Elision and Weak Form) |

| going to | /ˈɡɒnə/ | “Going” is often reduced, and “to” becomes /ə/. (Weak Form) |

| did you | /ˈdɪdʒuː/ | The /d/ in “did” and /j/ in “you” combine to form /dʒ/. |

| would you | /ˈwʊdʒuː/ | The /d/ in “would” and /j/ in “you” combine to form /dʒ/. |

| could you | /ˈkʊdʒuː/ | The /d/ in “could” and /j/ in “you” combine to form /dʒ/. |

| should you | /ˈʃʊdʒuː/ | The /d/ in “should” and /j/ in “you” combine to form /dʒ/. |

| is she | /ɪʃ ʃiː/ | The /s/ in “is” and /ʃ/ in “she” combine to form /ʃ/. |

| was she | /wɒʃ ʃiː/ | The /s/ in “was” and /ʃ/ in “she” combine to form /ʃ/. |

| does she | /dʌʃ ʃiː/ | The /z/ in “does” and /ʃ/ in “she” combine to form /ʃ/. |

| this shop | /ðɪʃ ʃɒp/ | The /s/ in “this” and /ʃ/ in “shop” combine to form /ʃ/. |

| that shop | /ðæt ʃɒp/ | The /t/ in “that” may influence the following /ʃ/ in “shop”. |

| white shoes | /waɪt ʃuːz/ | The /t/ in “white” may influence the following /ʃ/ in “shoes”. |

| dress shoes | /drɛʃ ʃuːz/ | The /s/ in “dress” and /ʃ/ in “shoes” may combine to form /ʃ/. |

| in the | /ɪn ðə/ | The /n/ in “in” may be nasalized due to the following /ð/ in “the”. |

Table 3: Elision Examples

This table demonstrates how sounds are omitted in connected speech to make pronunciation easier.

| Phrase | Connected Speech Pronunciation | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| next door | /ˈnɛks dɔːr/ | The /t/ in “next” is often elided. |

| old man | /ˈoʊl mæn/ | The /d/ in “old” is often elided. |

| grandma | /ˈɡrænmɑː/ | The /d/ in “grand” is often elided. |

| sandwich | /ˈsænwɪtʃ/ or /ˈsæmwɪtʃ/ | The /d/ in “sandwich” is often elided. |

| comfortable | /ˈkʌmftərbəl/ | The /ər/ sound is often reduced to a schwa, and the /t/ may be elided. |

| probably | /ˈprɒbəbli/ | The vowel in the second syllable is often elided. |

| chocolate | /ˈtʃɒklət/ | The second /o/ sound is often elided. |

| family | /ˈfæmli/ | The vowel in the second syllable is often elided. |

| camera | /ˈkæmrə/ | The second vowel sound is often elided. |

| every | /ˈɛvri/ | The vowel sound in the second syllable is often elided. |

| interest | /ˈɪntrəst/ | The /ər/ sound is often reduced to a schwa, and the /t/ may be elided. |

| library | /ˈlaɪbri/ | The second vowel sound is often elided. |

| February | /ˈfɛbruəri/ | The first /r/ sound is often elided. |

| government | /ˈɡʌvənmənt/ | The /ər/ sound is often reduced to a schwa, and the /n/ may be elided. |

| recognize | /ˈrɛkəɡnaɪz/ | The vowel in the second syllable is often elided. |

| generally | /ˈdʒɛnrəli/ | The vowel sounds in the second and third syllables are often elided. |

| literally | /ˈlɪtərəli/ | The vowel sounds in the second and third syllables are often elided. |

| temperature | /ˈtɛmprətʃər/ | The vowel sound in the second syllable is often elided. |

| vegetable | /ˈvɛdʒtəbəl/ | The vowel sound in the second syllable is often elided. |

| instance | /ˈɪnstəns/ | The /ənt/ sound is often reduced to /əns/. |

Table 4: Weak Form Examples

This table illustrates how function words are often reduced in connected speech.

| Word/Phrase | Strong Form | Weak Form | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | /eɪ/ | /ə/ | I need a pen. (/ə pɛn/) |

| an | /æn/ | /ən/ | I want an apple. (/ən ˈæpl̩/) |

| the | /ðiː/ | /ðə/ or /ði/ | The book is here. (/ðə bʊk/) |

| to | /tuː/ | /tə/ | I need to go. (/tə ɡoʊ/) |

| of | /ɒv/ | /əv/ or /ə/ | A piece of cake. (/ə piːs əv keɪk/) |

| for | /fɔːr/ | /fər/ or /fə/ | This is for you. (/fə juː/) |

| at | /æt/ | /ət/ | I’m at home. (/ət hoʊm/) |

| from | /frɒm/ | /frəm/ | I’m from Spain. (/frəm speɪn/) |

| is | /ɪz/ | /əs/ | He is here. (/əs hɪər/) |

| are | /ɑːr/ | /ər/ | They are coming. (/ər ˈkʌmɪŋ/) |

| was | /wɒz/ | /wəz/ | He was late. (/wəz leɪt/) |

| were | /wɜːr/ | /wər/ | They were happy. (/wər ˈhæpi/) |

| has | /hæz/ | /həz/ | He has arrived. (/həz əˈraɪvd/) |

| have | /hæv/ | /həv/ | They have left. (/həv lɛft/) |

| had | /hæd/ | /həd/ | I had gone. (/həd ɡɒn/) |

| do | /duː/ | /də/ | I do like it. (/də laɪk ɪt/) |

| does | /dʌz/ | /dəz/ | He does know. (/dəz noʊ/) |

| did | /dɪd/ | /dəd/ | I did go. (/dəd ɡoʊ/) |

| can | /kæn/ | /kən/ | I can help. (/kən hɛlp/) |

| could | /kʊd/ | /kəd/ | I could try. (/kəd traɪ/) |

Table 5: Contraction Examples

This table shows common contractions used in spoken and written English.

| Full Form | Contraction | Example Sentence |

|---|---|---|

| I am | I’m | I’m going to the store. |

| you are | you’re | You’re very kind. |

| he is/has | he’s | He’s a great teacher. |

| she is/has | she’s | She’s already finished. |

| it is/has | it’s | It’s a beautiful day. |

| we are | we’re | We’re going on vacation. |

| they are | they’re | They’re coming to the party. |

| is not | isn’t | It isn’t raining. |

| are not | aren’t | They aren’t here yet. |

| was not | wasn’t | He wasn’t happy. |

| were not | weren’t | We weren’t ready. |

| have not | haven’t | I haven’t seen him. |

| has not | hasn’t | She hasn’t arrived. |

| had not | hadn’t | We hadn’t known. |

| do not | don’t | I don’t understand. |

| does not | doesn’t | He doesn’t care. |

| did not | didn’t | She didn’t call. |

| cannot | can’t | I can’t believe it. |

| could not | couldn’t | We couldn’t go. |

| will not | won’t | I won’t forget. |

Usage Rules for Connected Speech

Understanding the rules that govern connected speech can help you predict how words will be pronounced in context. Here are some key rules:

- Linking: Link consonant sounds to following vowel sounds to create a smooth transition. Be aware of intrusive sounds (like /j/, /w/, and /r/) when linking vowels.

- Assimilation: Be aware of how sounds can change to match neighboring sounds, especially in terms of place of articulation.

- Elision: Recognize that certain sounds, particularly /t/ and /d/ at the end of words, may be dropped, especially before consonants.

- Weak Forms: Use weak forms for grammatical words in unstressed positions to maintain the rhythm of English.

- Contractions: Use contractions in informal contexts to make your speech sound more natural. However, be mindful of using contractions in formal writing.

There are also exceptions and special cases to consider. For example, some speakers may not use intrusive /r/ in non-rhotic accents, while others may use it consistently.

Similarly, the degree to which assimilation and elision occur can vary depending on the speaker’s accent and speaking style.

Common Mistakes in Connected Speech

Learners often make mistakes when trying to apply the rules of connected speech. Here are some common errors and how to avoid them:

- Over-articulating words: Pronouncing each word distinctly and separately can sound unnatural. Practice linking words together smoothly.

- Ignoring weak forms: Failing to use weak forms can make your speech sound overly formal and stilted.

- Misapplying assimilation: Applying assimilation incorrectly can lead to miscommunication. Be aware of the specific contexts in which assimilation occurs.

- Overusing contractions in formal contexts: Avoid using contractions in formal writing or speech.

- Not recognizing elision: Failing to recognize elision can make it difficult to understand native speakers.

Here are some examples of correct and incorrect usage:

| Mistake | Incorrect | Correct |

|---|---|---|

| Over-articulating | “I… am… going… to… the… store.” | “I’m going to the store.” (/aɪm ˈɡoʊɪŋ tə ðə stɔːr/) |

| Ignoring weak forms | “I am going to go.” (strong forms throughout) | “I’m going to go.” (/aɪm ˈɡoʊɪŋ tə ɡoʊ/) |

| Misapplying assimilation | “in correct” pronounced as /ɪŋ kəˈrɛkt/ (instead of /ɪn kəˈrɛkt/) | “in correct” pronounced as /ɪn kəˈrɛkt/ |

| Overusing contractions in formal contexts | “It’s important to consider the data.” (in a formal report) | “It is important to consider the data.” |

| Not recognizing elision | Hearing “next door” as /ˈnɛkst ˈdɔːr/ (instead of /ˈnɛks dɔːr/) | Hearing “next door” as /ˈnɛks dɔːr/ Identifying the elided /t/ sound. |

Practice Exercises

To improve your understanding and use of connected speech, try these exercises:

- Listening Practice: Listen to native speakers (e.g., in podcasts, movies, or TV shows) and pay attention to how they link words, use weak forms, and apply assimilation and elision.

- Reading Aloud: Read texts aloud, focusing on linking words smoothly and using appropriate weak forms.

- Shadowing: Listen to a recording and repeat what you hear as closely as possible, mimicking the speaker’s pronunciation and rhythm.

- Record Yourself: Record yourself speaking and listen back to identify areas where you can improve your use of connected speech.

- Minimal Pair Exercises: Practice distinguishing between words that sound similar due to connected speech phenomena.

Here are some specific exercises to try:

Exercise 1: Linking Practice

Read the following sentences aloud, focusing on linking the words together smoothly:

- I have an apple.

- Turn off the light.

- Look at the picture.

- Far away from here.

- Go out and play.

Exercise 2: Assimilation Practice

Read the following phrases aloud, paying attention to how the sounds change due to assimilation:

- in possible

- in big

- have to

- used to

- want to

Exercise 3: Elision Practice

Read the following words and phrases aloud, focusing on eliding the appropriate sounds:

- next door

- old man

- sandwich

- comfortable

- probably

Exercise 4: Weak Form Practice

Read the following sentences aloud, using weak forms for the grammatical words:

- I need a pen.

- The book is here.

- I want to go.

- A piece of cake.

- This is for you.

Exercise 5: Contraction Practice

Read the following sentences aloud, using contractions where appropriate:

- I am going to the store.

- You are very kind.

- He is a great teacher.

- It is a beautiful day.

- We are going on vacation.

Advanced Topics in Connected Speech

For advanced learners, there are several more complex aspects of connected speech to explore:

- Regional Accents: Different accents have different patterns of connected speech. For example, the use of intrusive /r/ varies significantly between accents.

- Speaking Rate: The faster someone speaks, the more likely they are to use connected speech phenomena.

- Formal vs. Informal Speech: Connected speech is more common in informal speech than in formal speech.

- Emotional Content: The speaker’s emotions can also affect their use of connected speech. For example, someone who is excited may speak faster and use more elision.

- Cross-linguistic Influence: Your native language can influence how you perceive and produce connected speech in English.

Understanding these advanced topics can help you fine-tune your listening comprehension and spoken fluency, allowing you to communicate more effectively in a variety of contexts.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between connected speech and pronunciation?

Pronunciation refers to how individual sounds and words are spoken, while connected speech refers to how these sounds and words change and link together in continuous speech. Connected speech builds upon pronunciation by adding another layer of complexity.

Why is connected speech so difficult to understand?

Connected speech can be difficult to understand because it involves changes to the sounds of words that are not apparent from their written form. These changes include linking, assimilation, elision, weak forms, and contractions, which can make it challenging to recognize individual words.

How can I improve my understanding of connected speech?

To improve your understanding of connected speech, practice listening to native speakers, read aloud, shadow recordings, and focus on recognizing and producing the different phenomena of connected speech, such as linking, assimilation, and elision.

Is it necessary to use connected speech when speaking English?

While it is not strictly necessary to use connected speech, mastering it will make your speech sound more natural and fluent. It will also improve your ability to understand native speakers, who naturally use connected speech.

Are there any resources that can help me practice connected speech?

Yes, there are many resources available, including online courses, textbooks, and language exchange partners. Listening to podcasts, watching movies and TV shows, and using pronunciation apps can also be helpful.

How does connected speech vary across different English accents?

Connected speech patterns can vary significantly across different English accents. For example, the use of intrusive /r/ is common in some accents but not in others.

Additionally, the degree to which assimilation and elision occur can vary depending on the accent and speaking style.

Conclusion

Mastering connected speech is an essential step towards achieving fluency in English. By understanding the different phenomena of connected speech, practicing regularly, and being mindful of common mistakes, you can significantly improve your listening comprehension and spoken fluency.

Whether you are a beginner or an advanced learner, the knowledge and skills you gain from studying connected speech will enable you to communicate more confidently and effectively in English.